Mashrabiya - It's five functional dimensions

Material culturalism is defined by Grier (1996) as the study of a subject matter that takes in the ‘biosocial environment’ from cultural buildings and landscapes. These valuable collections of artifacts reflect the lifestyles, interactions, environments and eras of people’s parents. Material culturists believe that the study of objects and artifacts and the circumstances in which they were made reveals unique perspectives and data that have not been well documented. Islamic Architecture is a rich cultural example with its delicate and geometrically advanced artifacts and production methods (Kaplan 2002).

Analysis into historic archetypes, specifically Mashrabiya, can significantly influence the current and future design of architecture facade treatments that could comply with the harsh environmental conditions in the Middle East. John Fenny (1974) poetically describes the silken masks of the Mashrabiya as symbolizing the “legendary mystery of the Orient.” Within Eastern cultures, this architectural construction is a three-dimensional, carved wood lattice structure whose primary function is to control visual privacy as well as temperature and lighting in interior spaces (Samuels 2011).

The Mashrabiya, as studied by Hassan Fathy (1986), represents an architectural screen that has five functional dimensions that are achieved through parametric variation in the material thickness and member density: controlling the passage of light, controlling the air flow, reducing the temperature of the air current, raising the humidity of the air current, and ensuring the privacy of the inhabitants within the Haramlak or Harim (women’s quarter) in the courtyard houses of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey and other eastern countries (see Abdelgelil 2006; Almurahhem 2011).

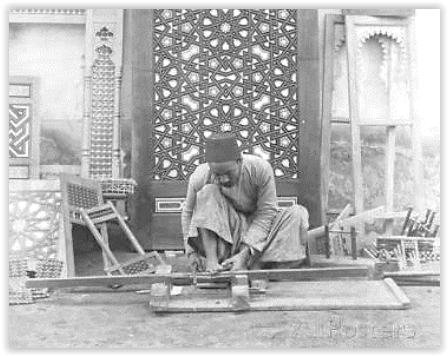

The Craft of Mashrabiya Making

This vernacular architectural construction requires significant craftsmanship in developing the individually hand-turned parts that work together in the overall assembly. As these craftsmen have become more and more scarce, the architecture has continued to become a caricature, losing much of its cultural value and passive performative functions.

The high cost of manufacturing these constructions and maintaining their performance is simply no longer feasible under the historic model of production (Abdelgelil 2006). Similar to the notion of Undrawable Architecture documented by Dritsas and Yeo (2013, 834), these constructions are “underpinned by tacit tectonic knowledge passed along generations which was never formalized, and a product of artisan craftwork of phenomenal complexity that was manually re-produced but never rationalized.”

Can manufacturing achieve the efficient reproduction of culturally frozen artefacts?

With the propagation of 3D printing technologies during the past two decades, the conservation of this architectural screen may potentially be found in the performative analysis of existing Mashrabiya in order to inform new parametric models. These can then be subsequently programmed into site-specific variants and produced via large-scale 3D printing. As digital fabrication technologies continue to proliferate throughout architectural design discourse and practice (Kolarevic 2003), the conception of a digital tectonic (Beesley and Seebohm 2000) becomes a powerful agent in the conservation of a historic architectural legacy.

The authors are interested in the implications for new digital craftsmen and fabricators whose knowledge can be harnessed in order to program relevant input data to generate assemblies that not only support performance from a functional vantage point but also inform a cultural trajectory. Interesting questions emerge regarding the replacement of manual labour with digital programmers: Will cultures allow for the replacement of the craftsman with the programmer? Can the cultural interactions be distilled down to quantifiable parameters that drive CNC equipment?

Notably, the authors are not directly interested in replicating historic Mashrabiya. In contrast, the aim is not to achieve the efficient reproduction of culturally frozen artefacts but instead to contribute to the evolution of the architecture, thus fostering new knowledge acquisition through observation, manufacture, and recursive analysis.

In the work presented in this paper, 3D-printed forms are developed parametrically and analysed. While this is a fully digital process, the work seeks to reconcile traditional cultures with contemporary manufacturing in the preservation of a traditional architectural archetype. This work additionally seeks to alleviate the impact industrialization has had on traditional culture and artisans, stabilizing the architectural construction and enabling future instantiations of Mashrabiya.

History of Mashrabiya

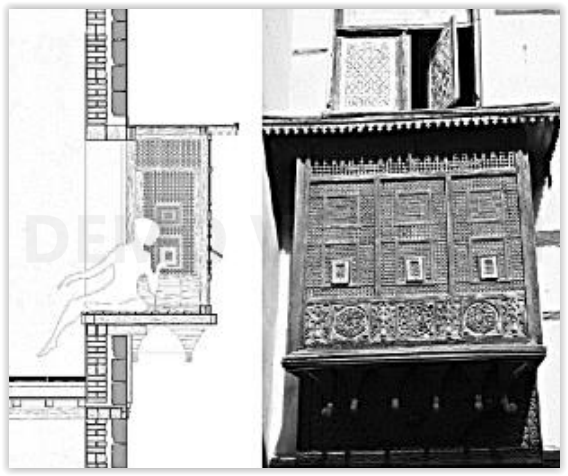

The Mashrabiya can historically be traced back to the Mamluk and Ottoman periods in Egypt (1517~1905) (Abdelgelil 2006). Since then, several culturally specific Mashrabiya have evolved according to their context and region. The definitions discussed here are related to the meaning and the functional and regional characteristics of the Mashrabiya.

A Mashrabiya is defined in the Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (Curl and Wilson 2015) as a timber ‘lattice screen’ that is often intricate, geometric and beautiful in Islamic architecture. The word Mashrabiya is argued to be derived from the Arabic verb Shareba, which means ‘to drink’ (Kenzari and Elsheshtawy 2003; Elshorbaji 2010).

This connection derives from the clay jars (Jara) containing water placed inside Mashrabiya inner shelves to passively cool the air current. Another important cultural connection of the Mashrabiya is Mashrafiya, derived from the Arabic word Sharefa, which relates to the high position of the openings and the fact that Mashrabiyas overlook lower spaces and passers-by (Almurahhem 2008; Aljowder 2014).

The form is also argued to overlap with another archetype known as Rawashen, which is found in the Hedjazi houses of Saudi Arabia (Almurahhem 2008) or the Shanasheel of Iran and Iraq. It is also thought to be linked to the Ottoman Empire Heremlik window grill termed Kafe (Sedky 1999). The term usually describes a projected bay or protected closed balcony with small openings so that the female inside the dwelling can look outside without being seen from the outside. As Sidawi (2012) clarifies, unveiling may violate the Islamic requirement for women to have privacy; the veil (head and body cover) enables them to remain covered to non-kinsmen. Outside the Middle East, Hui (2005) argues that Architecture treatments such as the Brise Soleil and Claustrum can also align with the functions and role of Mashrabiya within a facade.

Mashrabiya - A product for gender segregation?

Fathy’s (1986) five functional roles of Mashrabiya, as described above, define its essential functions. Environmentally speaking, Ficarelli (2009) explains how the window elements automatically activate a convective cycle that is capable of moving air masses from a higher pressure zone to that of a lower pressure zone.

Socially, the role of Mashrabiya evolved into a product for gender segregation, home seclusion and a veiling norm regulator. Nevertheless, it also mediates the architecture and interior experiences, allowing female occupants to observe exterior life without being observed themselves. Almurahhem (2008) adds another dimension through illustrating a poetic picture of the space behind the screen.

She visualizes it as a sensory experience provoker, where women not only socialize and gossip with other neighbouring females but may also use it to hear their children play outside or to call for road merchants to buy objects of daily use.

The relation between Mashrabiya and light

A complementary theme is the relation between Mashrabiya and light. Ghiasvand et al. (2008) explain how in Muslim culture light is a “symbol of divine unity”; Aljowder (2014) supports this view through her research on the relationship between light and visual privacy.

Both scholars agree that the Mashrabiya enables the passage of divine light which modifies other elements and forms patterns. Ghasvand (2008) suggests that with the right light coming through the pierced screen, the facade resembles lace. Light and shadow also add dynamic rhythms to architecture and its forms, giving texture to smooth surfaces. However, summer light can be harsh and cause severe temperature increases in the interior. As Samuels (2011) and Aljowder (2014) note, Mashrabiya screens fulfil this cultural need by responding to and blocking direct light and reducing solar gain.

Mashrabiya in Architecture

Much of the work done in the field of parametric design, as its etymology suggests, is in search of valid parameters that lend meaning and evaluation to the infinite variations that can be produced.

Often these parameters are found in the metric evaluation of different features in design and construction (Kolarevic and Klinger 2008). As Moussavi (2008) observed, this is similar to architectural design: “Architecture needs mechanisms that allow it to become connected to culture… Architecture progresses through new concepts that connect with these forces (visible or invisible), manifesting itself in new aesthetic compositions and affects.”

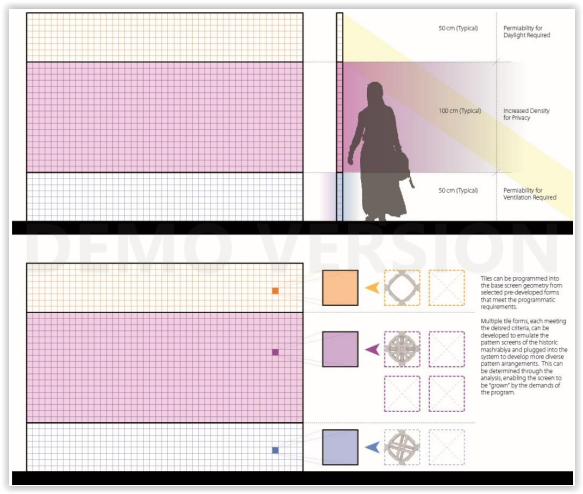

The traditions of the Mashrabiya unite a variety of functional, cultural and material conditions into an architectural manifestation of the boundaries between these dimensions. However, at the core of the design is an understanding that the human body acts as a reference point for the development of the product. The architecture protects the privacy of the Harim and enables the individual behind the screen to comfortably view exterior spaces.

As suggested by Beesley and Seebohm (2000), the digital tectonic designates an interest in the chemistry between the culture, the form, and manufacturing. As we look at the end of the Arts and Crafts movement in 1910 and leap towards the third industrial revolution, the cultural study informs a geometric ordinance system whereby highly tuned constructions are informed by cultural parameters and assembled in digital spaces.

Reflectively, the religious requirement for Muslim women to be veiled can be well satisfied through the use of a hybrid and parametric Mashrabiya as suggested in this research (see Figure 5). Looking directly into the manufacturing of these new constructs, 3D printing enables a new digital craftsman to emerge to fill the gap resulting from the loss of the traditional artisan.

These new digital craftsman are versed not only in the negotiation of digital space, but also in the negotiation of cultural, social, and performative functionality that must result from the manufacturing process.

What mashrabiya has in common with Japanese Tea Houses

Just as the Tea House in Japan is rooted in cultural, spatial, material, procedural and philosophical considerations, the Mashrabiya cannot escape the history of several hundred years that it emerged from. While a rather simplistic evaluation might suggest that it is a construction that is meant to maintain a boundary, we see an advanced evolution, avant-garde by some measures, that began to embed other considerations over time, including ventilation, daylighting, air cooling and humidity control.

Again, similar to the Tea House, you become aware of yourself and your proximity to spaces and the spaces become aware of you. In looking at the parametrization of the cultural conditions surrounding the Mashrabiya and its specific functionality, we hypothesize a new digital tectonic that mediates between the traditional culture and contemporary manufacturing. Ko and Liotta (2013, 329) posed a similar question when thinking about the Digital Tea House: “What would this diagrammatic and methodological approach produce when combined with a culturally meaningful function?”

The Digital Craftsman and the Traditional Artisan

As noted by Amit Zoran (2011, 324) in his Hybrid Basketry work, “contemporary 3D printing and traditional craft rarely meet in the same creation.” Zoran observed that the artifacts generated by 3D printing are intrinsically reproducible and this is in stark contrast with traditional craft.

Conversely, however, parametric tools are dominating the landscape and additive manufacturing enables the physical manufacture of completely unique operations just as easily as it allows for repetition. Just as the artisans of past epochs worked to understand both the tools and materials required to accomplish their craft, digital craftsmen are becoming aware of the functional limitations of varieties of technologies, embedding that knowledge, just as the craftsmen did, into the new digital constructions that constitute their craft.

The study of the historic Mashrabiya exposes a direct link with mathematical and geometric representations that can be directly engaged with in the programming of algorithmic designs. Digital craftsmen can take the opportunity to inform these traditional motifs with functional design parameters that can be adjusted through graphic algorithmic modelers (Grasshopper 3D).

Zones in the design are designated in the initial diagram (Figure 5), where daylighting, privacy and ventilation are articulated against the variable dimensions of the opening. Just as with Mashrabiya of the past, the occupant becomes the point of reference for the zoning, using the height of their eye level to set maximum privacy considerations. From this point, the geometric pattern is given a viscosity that is again driven by the algorithmic design process. The members gain thickness and dimensions, and are also blended together through the analysis in proximity to the maximum privacy datum; this geometric dimension is developed through the use of T-Splines (Figure 6).

3D printing - The ideal manufacturing process?

3D printing is selected as the ideal manufacturing process, as, at times, these constructions achieve a complexity that extends beyond multi-axis CNC milling. Once again the digital craftsman is tasked with embedding the limitations of the tool into the programming of the parametric model. Member thickness cannot fall below certain structural minimums without substantially weakening the overall construction.

Notably, the described digital model generates a rather static construction, with zones essentially stacking onto each other to fill the void in the construction. However, since these parameters have been programmed dynamically, the culture is able to evolve through the dynamic modification of the parametric model. The digital craftsman presides over a scenario where the user group (or culture) is able to intensify or dissolve the various parameters that define the Mashrabiya.

The digital craftsman becomes a facilitator for the level of privacy needed at the user level. Furthermore, as more cultural or functional variables (architectural programming, for example) emerge and are programmed into future instantiations of the Parametric Mashrabiya, the resultant forms will continue to evolve alongside the culture. In addition, the advantage of the units’ shape is linked to the fact that they can be digitally crafted to fit various patterns from both 2D surfaces and complex 3D interlaced geometries, some of which are too highly complex to be created using other mould-based manufacturing techniques.